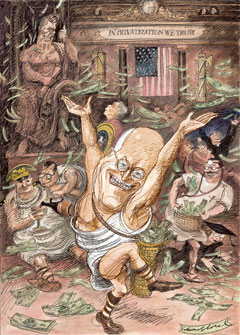

Illustration by Edward Sorel.

President and emperor, America and Rome: the matchup

is by now so familiar, so natural, that you just can't help yourself—it comes

to mind unbidden, in the reflexive way that the behavior of chimps reminds you

of the behavior of people. Everyone gets it whenever a comparison of Rome and

America is drawn—for instance, the offhand allusion to welfare and televised sports

as "bread and circuses," or to illegal immigrants as "barbarian

hordes." If reference is made to an "imperial presidency," or to

the deployment abroad of "American legions," no one raises an eyebrow

and wonders what you could possibly be talking about. Invoke the phrase

"decline and fall" and thoughts turn simultaneously to the Roman past

and the American present.

To be sure, a lot of Rome-and-America comparisons are glib, and if you're

looking for reasons to brush parallels aside, it's easy enough to find them.

The two entities, Rome and America, are dissimilar in countless ways. But some

parallels really do hold up, though maybe not the ones that have been most in

the public eye. Think less about decadence, less about military might—and think

more about the parochial way these two societies view the outside world, and

more about the slow decay of homegrown institutions. Think less about threats

from unwelcome barbarians, and more about the powerful dynamics of a

multi-ethnic society. Think less about the ability of a superpower to influence

everything on earth, and more about how everything on earth affects a

superpower.

One core similarity is almost always overlooked—it has to do with

"privatization," which sometimes means "corruption," though

it's actually a far broader phenomenon. Rome had trouble maintaining a

distinction between public and private responsibilities—and between public and

private resources. The line between these is never fixed, anywhere. But when it

becomes too hazy, or fades altogether, central government becomes impossible to

steer. It took a long time to happen, but the fraying connection between

imperial will and concrete action is a big part of What Went Wrong in ancient

Rome. America has in recent years embarked on a privatization binge like no

other in its history, putting into private hands all manner of activities that

once were thought to be public tasks—overseeing the nation's highways,

patrolling its neighborhoods, inspecting its food, protecting its borders. This

may make sense in the short term—and sometimes, like Rome, we may have no

choice in the matter. But how will the consequences play out over decades, or

centuries? In all likelihood, very badly.

A little more than 50 years ago, the Oxford historian

Geoffrey de Ste. Croix, a radical thinker and formidable classicist, decided to

take a close look at the change in connotation over five centuries of the Latin

word suffragium, which originally meant "voting tablet" or

"ballot." That change, he concluded, illustrated something

fundamental about Roman society and its "inner political evolution."

The original meaning went back to the days of the Roman Republic, which had

possessed modest elements of democracy. The citizens of Rome, by means of the suffragium,

could exercise their influence in electing people to certain offices. In

practice, the great men of Rome controlled large blocs of votes, corresponding

to their patronage networks. Over time Rome's republican forms of government

calcified into empty ritual or withered away entirely. Suffragium

meaning "ballot" no longer served any real political function. But

the web of patrons and clients was still the Roman system's substructure, and

in this context suffragium came to mean the pressure that could be

exerted on one's behalf by a powerful man, whether to obtain a job or to

influence a court case or to secure a contract. To ask a patron for this form

of intervention and to exert suffragium on behalf of a client would have

been a routine social interaction.

Now stir large amounts of money into this system. It is not a great

conceptual distance, Ste. Croix observes, to move from the idea of exercising suffragium

because of an age-old sense of reciprocal duty to that of exercising it because

doing so could be lucrative. And this, indeed, is where the future lies, the

idea of quid pro quo eventually becoming so accepted and ingrained that

emperors stop trying to halt the practice and instead seek to contain it by

codifying it. Thus, in the fourth century, decrees are promulgated to ensure

that the person seeking the quid actually delivers the quo.

Before long, suffragium has changed its meaning once again. Now it

refers not to the influence brought to bear but to the money being paid for it:

"a gift, payment or bribe." By empire's end, all public transactions

require the payment of money, and the pursuit of money and personal advancement

has become the purpose of all public jobs.

Looking back at the change, from ballot box to cash box, Ste. Croix composes

this epitaph: "Here, in miniature, is the political history of Rome."

The arc traced by suffragium covers not just the political history of

Rome but its social and military history. It goes to the heart of a question

that is only just starting to be asked in America: Where is the boundary

between public good and private advantage, between "ours" and

"mine"? From this question others follow: What happens when public

and private interests are not aligned? Which outsiders, if any, should be

allowed to put their hands on the machinery of government? How can governments

exert collective power if the levers and winches and cogs lie increasingly

outside public control?

The phenomenon with which all these questions intersect was called the

"privatization of power," or sometimes just "privatization,"

by the historian Ramsay MacMullen in his classic study Corruption and the

Decline of Rome (1988). MacMullen's subject is "the diverting of

governmental force, its misdirection." In other words, how does

it come about that the word and writ of a powerful central government lose all

vector and force? Serious challenges to any society can come from outside

factors—environmental catastrophe, foreign invasion. Privatization is

fundamentally an internal factor. Such deflection of purpose occurs in any number

of ways. It occurs whenever official positions are bought and sold. It occurs

when people must pay before officials will act, and it occurs if payment also

determines how they will act. And it can occur anytime public tasks

(the collecting of taxes, the quartering of troops, the management of projects)

are lodged in private hands, no matter how honest the intention or efficient

the arrangement, because private and public interests tend to diverge over

time.

Let's start with how the Roman system worked during

the many centuries when it actually did. By modern standards there were not a

great many officials or bureaucrats in Rome until late in the empire; the

administration and well-being of the capital and all the other cities and towns

depended on the talents and the largesse of the upper classes. A memorable

passage in Jérôme Carcopino's Daily Life in Ancient Rome describes what

happened every morning soon after Romans woke up, when all around the city

clients visited their patrons, and each was alert to the other's needs. On

those rare mornings when I've found myself sipping $15 orange juice at the Four

Seasons, I've enjoyed imagining the breakfast convergences at tables all around

me as an elite remnant of the old Roman dynamic. But to get Rome right you'd

have to extend the scene to every suburban Hyatt, every neighborhood diner;

you'd have to see these relationships governing every business transaction,

every trip to the doctor's office, every college application.

The patron-client relationship was so pervasive that it helps illuminate not

only Rome's social architecture but also, frequently, its way of conducting

foreign affairs. The term "client state" came into being for a

reason. As Julius Caesar fought his way through Gaul, he brought tribal

chieftains over to his side and described their professions of loyalty to

him—and thus to Rome—as those of clients to a patron. The relationships of the

Bush family with various world leaders have often been essentially personal.

The longtime Saudi ambassador to Washington, Prince Bandar bin Sultan bin

Abdulaziz, spent so much time at Bush family gatherings that he came to be

known as Bandar Bush.

Patronage spilled over into communal adornment; it was in fact inseparable

from it. The Roman magnates competed with one another to endow the capital with

improvements. Rome's wealthiest class, the senatorial aristocracy, constituted

by one estimate two-thousandths of 1 percent of the population; then came the

equestrian class, with perhaps a tenth of a percent. Collectively these people

owned almost everything. Americans are well aware of the nation's worsening

income inequality, with those in the top 1 percent earning nearly 50 times more

a year than those in the bottom 20 percent. The average C.E.O. earns more than

400 times as much as a typical worker. In Rome, the gap between the elite and

everyone else was on the order of 5,000 or 10,000 to 1. ("Nothing is more

unfair than equality," observed a very comfortable Pliny the Younger, who

would have felt at home in many Washington circles.) The expectation in Rome

was that affluent citizens, as individuals rather than as taxpayers, should

provide for community needs. Did the city require another aqueduct? New roads?

A stadium? Some magnate would surely provide it—in return, implicitly, for a

measure of public power, and, of course, for ample public recognition.

Inscriptions on countless marble fragments attest to such generosity—an early

version of "Brought to you by … "

On Rome's edifice of private giving—whether with the seemliness of an Andrew

Carnegie or the vulgarity of a Donald Trump—an empire was built. The Roman

system was a remarkable contrivance. But it contained the seeds of its own

destruction. For one thing, it fostered an expectation that "others"

would always provide. If public amenities came into being through private

munificence—and if these in turn served to enhance private glory—then why

should the public pay for their upkeep? This way of doing business "did

not work for the common benefit of the overall urban fabric," writes one

historian, much less nurture a sense of common purpose and shared

responsibility. I've seen the same mind-set at work within my state,

Massachusetts, in hardscrabble mill towns whose philanthropic founding families

have departed, where local taxpayers resist the idea that support of libraries

and hospitals must now rest with the community as a whole. Moreover, even at

its most uncorrupted, the patronage system was greased by small considerations:

"It was a genial, oily, present-giving world," Ramsay MacMullen

writes.

Now gradually remove from all this any sense of public

spirit or public obligation and replace it at every level of government—in the

barracks, the courts, the city councils, the provincial prefectures—with an

attitude of "What's in it for me?" To see this transition in starkly

American terms, first consider the idealistic sensibility of a letter of

introduction written from France by Benjamin Franklin to George Washington in

1777, on a matter of public business: "The Gentleman who will have the

Honour of waiting upon you with this Letter is the Baron de Steuben He goes to

America with a true Zeal for our Cause, and a View of engaging in it and

rendring it all the Service in his Power. He is recommended to us by two of the

best Judges of military Merit in this Country."

For comparison, consider the more contemporary sentiments in proposals and

e-mails from Jack Abramoff's lobbying team, also on a matter of public

business: in this instance, mounting a political operation to reopen the

Speaking Rock Casino, in Texas, in return for millions of dollars in fees and

political contributions. In 2002, the Abramoff team explained to its clients

the Tigua Indian tribe: "This political operation will result in a

Majority of both federal chambers either becoming close friends of the tribe or

fearing the tribe in a very short period of time. Simply put, you need 218

friends in the U.S. House and 51 Senators on your side very quickly, and we

will do that through both love and fear." Abramoff, who would eventually

plead guilty to corruption charges, explained to his clients that favors might

need to be topped off: "Our friend … asked if you could help (as in cover)

a Scotland golf trip for him and some staff (his committee chief of staff) for

August. The trip will be quite expensive … (we did this for another member—you

know who) 2 years ago. Let me know if you guys could do $50 K."

This is the story MacMullen traces, as throughout the empire a lubricious

glaze of venality came to coat every governmental surface. I don't know how it

would be phrased in Latin, but one of Jack Abramoff's e-mails ("Da man!

You iz da man! Do you hear me?! You da man!! How much $$ coming tomorrow? Did

we get some more $$ in?") captures some of the spirit of public service in

the late empire. What accounts for the change? No one factor but a combination

of many, including the sheer growth in the government's administrative reach

and the resultant transformation of "public service" from the

rotating duty of the upper class into a lifelong career for a larger group. A

bronze plaque was affixed to a public building in Timgad, in Numidia (now

Algeria), a city built as a bastion against the Berbers, which literally

provided a recommended price list for payments to ensure the prosecution and

success of various kinds of litigation. We don't have anything exactly like

that now, I suppose, but have you ever received a fund-raising solicitation

from one of the political parties, with degrees of access and other perquisites

tied to specific contribution levels? Here's the Republican contribution

hierarchy for the 2004 elections, which I can't help visualizing as a Numidian

bronze plaque:

$300,000 Super Ranger

$250,000 Republican Regent

$200,000 Ranger

$100,000 Pioneer

Time and again imperial decrees throughout the later empire attempt to put a

stop to skimming, extortion, and the illicit use of office—or, failing that, to

codify what may be permissible. But the emperors are standing athwart the tide,

and the imperial pronouncements have a doomed, forlorn, ritual feel to them.

Modern newspaper headlines along the lines of congress votes new

curbs on lobbyists convey something of the same formulaic quality.

How does the buying and selling of influence hollow out government? Some

make the argument that, whatever its moral shortcomings, the profit motive,

including its corrupt dimension, is in fact an efficient economic mechanism: it

gets things done. As one character argues in the movie Syriana, corruption

is why we win. But as MacMullen points out, for a government to be

effective on a national or an imperial scale, there needs to be a presumption

that information is traveling accurately up and down the administrative chain

of command, and that every link in the chain between a command and its

execution is reliable and strong. Putting power into private hands frequently

ends up breaking that link. Making the exercise of power contingent on payment

by definition breaks the link.

Privatization today often makes itself felt in ways

that would have turned no heads in ancient Rome. Naturally, it still includes

influence peddling and bribery and the buying and selling of public office.

Former California representative Randy "Duke" Cunningham, now in

jail, infamously drafted a "bribe menu" on official stationery,

linking the size of defense contracts he would deliver with the size of

payments he received. Representative Bob Ney, implicated in the Abramoff

scandals, resigned his congressional seat, having been reportedly warned by his

majority leader that if he stayed and lost his seat for his party, he

"could not expect a lucrative career on K Street"—that is, he would

jeopardize any future as an influence peddler, what the Romans called a suffragator.

(All for naught in Ney's case: he's now in jail.) And as in Rome, privatization

still includes turning over government departments to incompetent cronies,

empowering private individuals at the expense of public intentions. The Federal

Emergency Management Agency, staffed by inexperienced political appointees and

unable to cope with the Hurricane Katrina disaster, is only the most prominent

instance.

But the dominant form of privatization today is something relatively new, at

least in its dimensions. Government on its stupendous modern scale—regulating

every industry; re-distributing treasure from one sector of society to another;

forecasting the weather and mapping the human genome—simply did not exist in

ancient Rome. Because the extent of government is larger, privatization has

more scope. Its most pervasive form is perfectly legal: the hiring of

profit-making companies by the thousands to do government jobs. The ostensible

motives may be pure, but the result is to diminish government's capacity. For

one thing, government loses the ability to perform certain functions; it's hard

to un-privatize. Moreover, the effect in every case is to insert an

independent agent, with its own interests to consider and protect, into the

space between public will and public outcome—a dynamic that represents a

potential "diverting of governmental force" far more systemic and

insidious than outright venality.

Privatization along these lines has occurred most decisively in America and

Britain. In 1976 a book was published in the United States called The Shadow

Government, written by Daniel Guttman and Barry Willner; its subtitle spoke

ominously of "the government's multi-billion-dollar giveaway" of

decision-making authority. Government agencies, the authors warned, were

farming out various functions to high-priced consultants, secretive think

tanks, and corporate vested interests—accountable to no one! And

"outsourcing" was not the only issue. Some parts of the government,

they went on, might even be sold off completely—turned into private businesses!

The process was "cloaked in contractual and other formal approvals by the

various executive departments," but make no mistake: it amounted to

nothing less than a "drive to merge Government and business power to the

advantage of the latter."

A little more than a decade later, the shadow government was out of the

shadow. There is a plausible rationale for privatization—one that often makes

sense in the short run and for specific tasks. Private contractors may be able

to operate more efficiently than government agencies do. Marketplace signals

may prove to be more direct and powerful than bureaucratic ones. And why

shouldn't the government hire outside specialists for help with certain chores,

the way any household or business does? In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan created a

presidential commission on privatization to study not how the boundary between

public and private might be bolstered but how it could be pushed out of the way

even further, to give private interests more opportunity to move in. The same

idea surfaces in the "re-inventing government" movement taken up by

the Clinton administration: "We would do well," one proponent wrote,

"to glory in the blurring of public and private and not keep trying to

draw a disappearing line in the water." Since then privatization has

affected every aspect of American public life.

The most visible surge in government outsourcing has

come in the realm of the military. Rome hired barbarian soldiers to make up for

its acute manpower shortages (not a good long-run solution, history would

show). America is hiring private military companies for the very same

reason—not the Visigothi or the Ostrogothi but the Halliburtoni and Wackenhuti.

Conan the Barbarian has become Conan the Contractor. But in fact every facet of

"personal security" is increasingly in the hands of private business.

It was not until the mid–19th century that America's urban governments, by

setting up local police forces, managed to make an ordinary person's safety a

matter of real public responsibility. This was a major advance, though perhaps

only temporary. No one with money relies on such guarantees any longer (nor did

they in Rome, where police forces as we know them were virtually nonexistent).

More and more people have withdrawn into protected enclaves. Private security

is a major growth industry; in 1960 there were more police officers than hired

security guards in America, whereas today private guards outnumber the police

by a margin of 50 percent. Individuals may owe nominal allegiance to a town or

a state, but their true oath of fealty is to Securitas or Guardsmark.

One of the chief obligations of any government is simply to dispense

justice—to resolve disputes, oversee legal business, mete out punishment. These

functions were once held in private hands. After a stint as a public

responsibility, they are now migrating back. Lawyers and clients increasingly

shun the civil courts—congested, expensive, fickle—and instead buy themselves

some private arbitration, provided by a growing cadre of profitable

"rent-a-judge" companies. As for the criminal-justice system, those

sentenced to prison may very well do their time in a private facility, run on

behalf of state and federal governments and operated by a company with some

former public official in its management to grease the wheels. Faced with

rising numbers of inmates, and unwilling to raise taxes to build more public

prisons, governments at all levels have found that the easy, cost-effective way

is to turn the prison industry over to the private sector: to a behemoth such

as the Nashville-based Corrections Corporation of America, or to one of many

smaller companies.

America's public colleges and universities are fast

losing their public character. These institutions were created under the terms

of an act signed by Abraham Lincoln in 1862, providing federal land grants to

the states as a basis for public financing of higher education. But state

support is diminishing. Nationwide, state legislatures are picking up only

about two-thirds of the annual cost of public higher education. For the

University of Illinois, the figure is 25 percent. For the University of

Michigan, it's 18 percent. What makes up the difference in funding? To a large

degree it's money from private donors and private corporations, creating an

incipient "academic-industrial complex" at public and private

institutions alike. You can't escape the signs. At the University of California

at Berkeley, one administrator is officially known as the Bank of America Dean

of the Haas School of Business. But for a conviction or two, Rice University

would have had a Ken Lay Center for the Study of Markets in Transition, endowed

by the late former chairman of Enron. Much money for universities comes with

strings attached—for instance, the power to push research in certain directions

and perhaps away from others, and the ownership of patents deriving from

sponsored research.

Sociologists have a term for what is occurring: they call it the

"externalization of state functions." Water and sewage systems are

being privatized, as are airports and highways and public hospitals. Voucher

programs and charter schools are a way of shifting education toward the private

sector. The protection of nuclear waste is in private hands. Meat inspection is

done largely by the meatpacking companies themselves. Americans were up in arms

last year when they learned that DP World, a company in the United Arab

Emirates, would soon be in control of the terminals at half a dozen major U.S.

seaports—only to discover that the privatization of terminal operations at

American ports had begun three decades ago, and that 80 percent of them were

already operated by foreign companies, the largest of which is Chinese. Serious

proposals to privatize portions of Social Security have been on the table, and

the new Medicare prescription-drug plan effectively puts an enormous government

program into the hands of private insurance and drug companies.

Many services that used to be provided free of charge

now must be paid for—government by user fee. Detailed statistical data from the

Census Bureau and other agencies were once available to everyone; now they're

being sold, mainly for marketing purposes, and often at prices that only

private corporations can afford. The vaults of the Smithsonian were once open

to documentary-film makers regardless of provenance and financing. Now an

agreement between the Smithsonian and the cable company Showtime has created

something called the Smithsonian Networks, which has jurisdiction over, and

priority access to, certain kinds of material.

Is there any government function that can't be transferred to some private

party? A considerable amount of tax collection is now done, in effect, by

casinos; rather than raise taxes to pay for services, legislatures legalize

gambling and then take a rake-off from the profits earned by private casino

companies. It's "tax farming" for the modern age, recalling the hated

Roman practice of selling the right to collect taxes to private individuals

(including the apostle Matthew in the Gospels), who were then allowed to keep

anything over what they had agreed to collect for the government. As the recent

revelations about torture have made clear, even official interrogations for

national-security purposes have been outsourced—in this instance to other

countries through the process known as "extraordinary rendition." The

sale of naming rights for public facilities and other amenities attracts notice

mostly for the ungainly nomenclature that results—mutants such as the

Mitsubishi Wild Wetland Trail, at the New York Botanical Garden, in the Bronx,

and Whataburger Field, in Corpus Christi. To attract more corporate

underwriting, the Department of the Interior has proposed that America's

national parks be liberally opened up to the sale of naming rights. No one is

suggesting that there will soon be a J. Crew Cape Cod National Seashore. But

might there be a Sherwin-Williams Painted Desert Trailhead?

An analyst at Johns Hopkins observes,

"Contractors have become so big and entrenched that it's a fiction that

the government maintains any control." One obvious recent example is the

rebuilding effort in Iraq. To supply the army or provide other services,

traders and contractors often traveled with Roman legions; Julius Caesar had

such a person with him during the Gallic Wars, explicitly "for the sake of

business." There may have been no alternative to giving the reconstruction

job in Iraq to private corporations, including giant combines such as Bechtel

and Halliburton, but the result has been an effort that defies management or

accountability. The evidence of widespread corruption in the Iraq rebuilding

effort is beyond dispute. Corruption aside, private companies are exempt from

many regulations that would apply to government agencies. The records of private

companies can't be obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. They can

use foreign subsidiaries to avoid laws meant to restrain American companies.

Before the war, Halliburton itself used subsidiaries to do business with Iran,

Iraq, and Libya, despite official American trade sanctions against all three

countries.

More and more secret intelligence work—translation, airborne surveillance,

computing, interrogation, analysis, reporting, briefing—is being farmed out to

private entities. Not only is the intelligence community becoming further

fragmented, but, because the new jobs pay so well, a "spy drain" is

drawing officers out of the public sector and into the private market. And the

drain isn't restricted to spies: at least 90 former top officials at the

Department of Homeland Security and the White House Office of Homeland Security

are now working for private companies in the domestic-security business.

Meanwhile, the government seems poised to turn the job of border police over to

multi-national contractors, a task that will in turn be subcontracted out to

dozens of smaller companies. Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Boeing, and Northrop

Grumman were among the corporations that indicated they would submit bids to

build a high-tech "virtual fence" along the Mexican border, with an

array of motion detectors, satellite monitors, and aerial drones. (Boeing

eventually won.) A Homeland Security official conceded the abdication of

government leadership, saying to the companies, "We're asking you to come

back and tell us how to do our business."

One study from the late 1990s suggests that the "privatization

rate"—the rate at which public functions are being outsourced—is roughly

doubling every year. On paper the federal workforce nationwide, leaving the

military aside, appears to total about two million people. But if you add in

all the people in the private sector doing essentially government jobs with

federal grants and contracts, then the figure rises by 10.5 million. The

commercialization of government probably explains why so many Washington

entities are now referred to as shops: "lobby shop,"

"counterterrorism shop." There's no question that in certain ways the

private sector can outperform the public sector. Users of Federal Express, U.P.S.,

and DHL would sooner renounce citizenship than go back to relying only on the

U.S. Postal Service. The problem is the cumulative effect of privatization

across the board—projected out over decades, over a century, over two—and the

leaching of management capacity from government. This is the same "misdirection"

of government force that MacMullen discerns in Rome: easier to observe in

retrospect, when the whole film is available, than in the brief, real-time clip

any of us is allowed to see.

The activities of government are, in effect, being

franchised out. You can't help lingering over the concept of

"franchise," wondering what a latter-day Geoffrey de Ste. Croix would

make of it. Like suffragium, the word originally had to do with notions

of political freedom and civic responsibility. Derived from the Old French word

franc, meaning "free," it later came to be associated with the

most fundamental political freedom of all: to exercise your franchise meant to

exercise your right to vote. Only much later, in the mid–20th century, did the

idea of being granted "certain rights" acquire its commercial

connotation: the right to market a company's services or products, such as

fried chicken or Tupperware. Today, to have a franchise on something is in

effect to have control over it.

Looking at the history of the word, it's tempting to write this epitaph:

Here, in miniature, is the political history of America.

Buy

Are We Rome? on Amazon.com.

Cullen Murphy is Vanity Fair's

editor-at-large.