http://www.nyobserver.com/2007/happy-bedfellows-spend-big-mayor-s-plan/

This article was published in the June 17, 2007, edition of

The New York Observer.

Happy Bedfellows Spend Big for Mayor’s Plan

by Matthew Schuerman Published: June 12, 2007

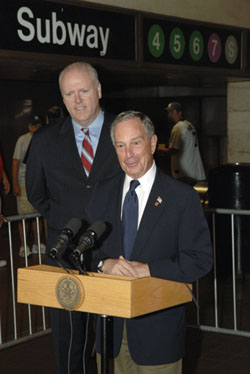

Photo:

nyc.gov Mayor Michael Bloomberg

announces the support of Congressman Joseph Crowley, left, for his long-term

environmental plan.

Photo:

nyc.gov Mayor Michael Bloomberg

announces the support of Congressman Joseph Crowley, left, for his long-term

environmental plan.

Blue-chip companies, public-interest groups and private

foundations have spent more than $2 million since late April to support Mayor

Bloomberg’s environmental sustainability plan, including its congestion-pricing

push, according to participants, outspending opponents by more than 10 to 1.

The money, while far from guaranteeing the votes needed to

get the plan passed in the State Legislature by its June 21 recess, has enabled

proponents to overwhelm the paid-media market with cable-television

commercials, well-connected lobbyists and a top-shelf public-relations company.

Last month, for example, the Partnership for New York City,

an organization of business executives, and Environmental Defense spent

$550,000 to repeatedly run a 30-second television advertisement on cable

stations in New York and Albany, according to Kathryn Wylde, the president of

the partnership. The Real Estate Board of New York, the industry lobbying

group, raised an amount somewhere in the six figures from its members to put on

an ad of its own last week and this week, according to spokesman Frank Marino.

A broad coalition of supporters will start airing a third ad on Wednesday and

announced they will send out 380,000 mailers touting the benefits of the plan.

Ms. Wylde said that the partnership had spent “over $1

million” in support of PlaNYC, which is the Mayor’s program to help cope with

the expected one million new residents the city will see by 2030, and estimated

that all groups favoring congestion pricing had contributed between $2 million

and $3 million.

For example, the Campaign for New York’s Future, the

coalition that was set up by supporters right after the Mayor unveiled his plan

on April 23, has hired Rubenstein Communications, a company founded by

public-relations czar Howard Rubenstein—who represents, among others, the

Mayor’s media company (and The Observer, no less).

Opponents have hired Richard Lipsky, a tireless street

fighter who has taken on many quixotic causes over the years, representing the

bodegas, nightclubs, grocery stores and haulers. For this issue, he has been

holding press conferences on street corners and in front of supermarkets.

While the pro side sports a new, custom-made Web site, with

links to the television commercials and a sign-up form, opponents have Mr.

Lipsky’s blog for a related organization called the Neighborhood Retail

Alliance, which is hosted by Blogspot.com.

Whether that financial and institutional support for the

proposed $8 fee for driving into Manhattan south of 86th Street is enough to

get the proposal passed in Albany is another matter. The speaker of the State

Assembly, Sheldon Silver, the Democrat from lower Manhattan who blocked the

Mayor’s last big public campaign—the West Side stadium—said on June 11 and 12

that he did not expect the congestion-pricing bill would come up before the end

of the normal session but allowed that he would call a special session over the

summer if necessary.

“The one thing that folks have to recognize in this town is

that it is not about editorials, it is not about the number of blue-chip

organizations behind you, it is not the money, although they are helpful,” said

Walter McCaffrey, the political consultant working for an opposition group

called Keep N.Y.C. Congestion-Tax Free, affiliated with the Queens Chamber of

Commerce. “You have to have a message that resonates with the public, and their

message is not resonating.”

Opponents have raised “about $150,000” over the past year,

according to Mr. McCaffrey. He said that the funders include owners of parking

garages in Manhattan as well as two real-estate developers, at least one of

whom has property both in and outside the congestion zone.

He points, in particular, to a Quinnipiac University poll

taken in the days after Mayor Bloomberg proposed congestion pricing that showed

that the public opposed the idea by 56 to 37 percent. Supporters of congestion

pricing counter that surveyors neglected to mention that the revenue from the

fees—an estimated $380 million annually to start and growing after that—would

go toward improving subway and bus service.

PART OF THE REASON THE PROPONENTS have grown such deep

pockets is that they represent a broad constituency. Congestion pricing is one

of those magical political issues that has captured the minds of both the grass

roots and the business elite because it has something for pretty much everyone:

the Straphangers Campaign has signed on because the fees provide revenue to

improve the transit system; business groups believe that congestion is eating

up workers’ time in traffic and adding costs onto deliveries.

The environmental and health benefits expected to result

from lighter traffic are fairly modest—congestion pricing will reduce pollution

between 2 and 4 percent, according to the Mayor’s figures—but PlaNYC includes

126 other initiatives, geared toward reducing greenhouse gases by 30 percent by

2030. Environmental and health groups, then, have also thrown support behind

the plan.

Indeed, the issue has attracted such an unusual combination

of players that many who opposed the Mayor on the West Side stadium now find

themselves supporting him, from West Side Assemblyman Richard Gottfried to John

Raskin, a community organizer who was the spokesman for the grass roots during

the stadium fight; from Public Advocate Betsy Gotbaum to Straphangers Campaign

staff attorney Gene Russianoff. (REBNY and the Partnership for New York City,

however, supported the Mayor in the stadium fight.)

“The stadium was a model of how to turn off New Yorkers and

PlaNYC was a model of how to engage people,” said Mr. Russianoff, of the dozens

of meetings the Bloomberg administration held with advocacy organizations during

the fall and winter while they were formulating PlaNYC. “They wanted other

people to own the process, and that is the genie in the bottle. I think groups

have been very active and aggressive in promoting the plan as a result. We have

largely dropped most of what we were planning to do in May and June to focus on

this.”

In addition to pressing their underpaid staffs into labor on

PlaNYC, nonprofit supporters have also dragged in some extra cash: Some eight

foundations who had existing ties with transportation and environmental

advocacy groups have committed $835,000 so far toward the campaign, according

to Chris Jones, vice president for research at the Regional Plan Association,

which supports PlaNYC (and which opposed the stadium).

“We gave a $150,000 grant to be used by the R.P.A. to

support a public education campaign on the general outlines of the Mayor’s plan

and the general desirability of it,” said Conn Nugent, the executive director

of the J.M. Kaplan Fund, which in the past has supported the Straphangers

Campaign, Transportation Alternatives and a poll, conducted this spring,

commissioned by the Partnership for New York City that asked drivers their

opinion on congestion pricing and what other transit options they have.

Because of restrictions on foundation grants, these funds

cannot be used for lobbying on a particular bill, just an issue in general. But

strangely, it is on lobbying that the two sides may be most evenly matched.

Environmental Defense is paying Patricia Lynch, a former aide to Assembly

Speaker Silver, $30,000 over two months to lobby the State Legislature,

according to lobbyist disclosure records online; the partnership has hired

Terri Thomson, a former city Board of Education member from Queens, for $5,000

a month.

Meanwhile, lobbyist Brian Meara and Kenneth Riddett, former

chief counsel to Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno, are each making $10,000

working for the opponents.

However, organizations that already have lobbyists in Albany

are pressing them into service in this cause, and for the most part that means

more heft on the pro side than on the con.

“I would say that for every dollar we can raise, they have

20 or 25, if not more,” Mr. Lipsky said. “And yet, when we get outside of

Manhattan, the poll numbers are extraordinary.”

MR. LIPSKY CONTENDS THAT ALL OF this money—and even all of

the supporters’ organizations—are not buying them support. And just as the

Mayor learned from the stadium fight that real power resides in unusual places,

so too may he be surprised this time around.

At the first Legislative hearing on congestion pricing on

June 8, the hearing room, in the stately Association of the Bar of the City of

New York building in midtown, was packed with hundreds of supporters of

congestion pricing wearing “I Breathe & I Vote” T-shirts. They ride their

bikes to work, or eat vegetarian, or strive to leave a zero carbon footprint in

their daily lives—in other words, they looked like the future.

By contrast, one of the legislators who kept giving Mayor Bloomberg a hard time seemed pretty old-fashioned: He said he didn’t have a computer and that he did not use an E-ZPass to pay tolls—even though doing so would give him a discount. On the other hand, that legislator, Herman (Denny) Farrell Jr., an Assemblyman from Upper Manhattan, is one of the most powerful Democrats in the state.